[ad_1]

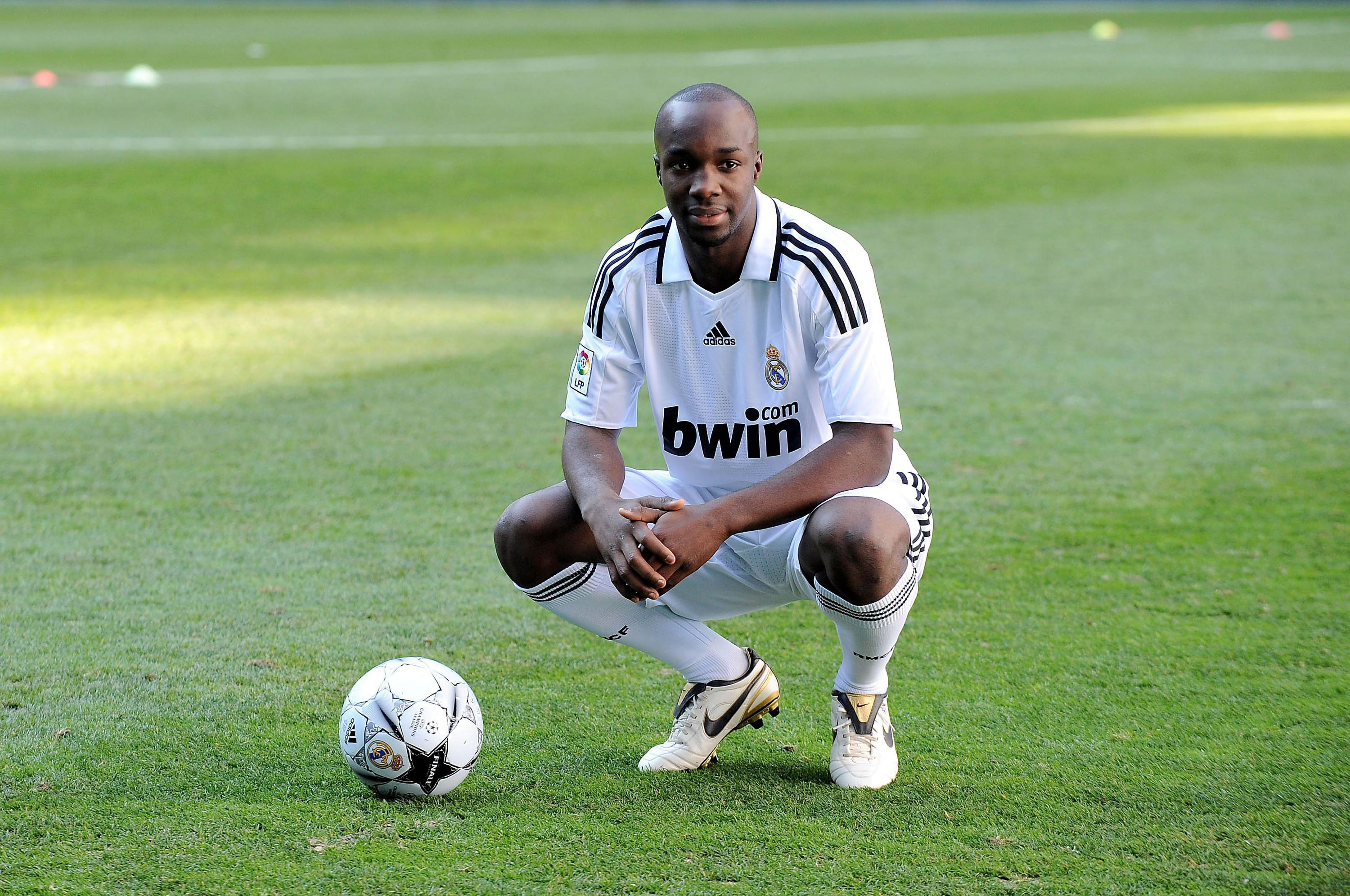

The future of the entire football transfer system is set to be decided after a European Union court found in favour of Lassana Diarra in his case against FIFA relating to a 2014 transfer move.

The issue was whether Diarra and any club who wanted to sign him were liable to pay reparations to Lokomotiv Moscow after Diarra unilaterally terminated his contract (that is, he terminated it himself, not Lokomotiv), citing unpaid wages.

FIFA rules set out that in that scenario, compensation should be paid to Lokomotiv by both Diarra and his future club – in this case, Belgian side Charleroi, which is why the case has been heard in Belgium.

What have the EU decided in the Lassana Diarra case?

Nothing final yet – the court of justice of the European Union (CJEU) were asked to give their opinion on the Diarra case, with a final decision to be made by the Belgian appeal court.

The response to the outcome was predictably mixed. Players’ union FIFPro went very big on hailing it as a landmark case, while FIFA and the European Club Association (ECA) both played down the effects it might have.

The reality may be somewhere in between, but – as it stands, pending the Belgian courts’ final decision – probably closer to FIFA’s read on things.

Some headlines might say that FIFA’s transfer rules are unlawful under EU law, but the wording of the judgment made clear that the commission’s view was that it is only some of those regulations that run afoul – namely, the ones that apply to cases like Diarra’s.

The best features, fun and footballing quizzes, straight to your inbox every week.

It is relatively unusual for players to find themselves in the same position as Diarra, and there are currently other means that clubs may be able to use to make it difficult for players to walk away from their contracts willy-nilly. But the big question is how far the courts will go in their verdict on that.

Diarra’s victory here may only have limited consequences if the full context of the CJEU’s judgment is taken into account.

VIDEO: Why Lee Carsley Might Fix England

That’s because although the EU requires sporting bodies to operate within their rules, and generally take a dim view of attempts to place restrictive anti-competition clauses in contracts, they have also long acknowledged that there is a need to offer some protection and certainty to sporting institutions to help protect the integrity and stability of the competitions.

Even when finding in Diarra’s favour, the CJEU reiterated that in their judgment here, saying: “Restrictions on the free movement of professional players may be justified by overriding reasons in the public interest consisting in ensuring the regularity of interclub football competitions, by maintaining a degree of stability in the player rosters of professional football clubs.â€

The issue was that – in the panel’s view, and subject to a Belgian appeal court agreeing – FIFA’s current rules in cases like Diarra’s ‘nonetheless seem … to go beyond what is necessary to pursue that objectiveâ€.

What does this mean for the transfer system?

The Belgian courts will now decide to what extent FIFA have gone too far and to what extent their rules need to be revised.

FIFA and the ECA seem to think that if necessary, those specific rules can simply be tweaked to bring them in line with EU law, without further implication on the rest of their regulations.

Organisations like FIFPro are likely to push for things to be taken further, allowing players far greater freedom of movement that may bring the transfer system as we know it crashing down. Quite what a new system might look like is hard to say, but it would be significantly more weighted in players’ favour.

There’s also a middle ground, where players may be allowed greater opportunity to unilaterally break their contracts to pursue a move, but only if they are given ‘just cause’ to do so. If that happens, ‘just cause’ may not include factors like ‘I’m not getting picked’ or ‘I just want to go to a bigger club’: it could require something like wages going unpaid, as happened with Diarra.

The timescales on Diarra’s case should also be noted. It has taken ten years since his initial dispute just to get this far, and there’s still another hearing to be completed.

Players’ careers are short, and, rightly or wrongly, the threat of tying players up in litigation for extended spells if they tear up their contracts may be a disincentive for a lot of players, whatever the final outcome of the Diarra case.

If the Belgian court does stay limited in its scope to focus on the specific circumstances Diarra found himself in, it seems likely that there will be future tests of the transfer system more broadly at some point down the road; when exactly that day would come is anybody’s guess.

[ad_2]

Source link