[ad_1]

“They took a dead man and cast him into the well, and then filled it up with stones.”

So declares the 800-year-old Norse Sverris Saga, an accounting of the rise and reign of King Sverre Sigurdsson, who went on to rule Norway from 1184 until his death in 1202 CE.

Now, thanks to the efforts of a team of scientists from Scandinavia, Iceland, and Ireland, we have direct, tangible evidence that the Well Man really existed – in the form of bones, freshly analyzed, discovered at the bottom of the very well described.

The Well Man is barely a throwaway line describing a conflict that took place in 1197 CE – a corpse thrown into a castle well by an invading force, probably to make any water therein undrinkable by decaying in it. But that throwaway line has suddenly become one of the most significant in the saga – by being the first incident in such a document ever to be linked to real, historical remains.

The bones in question represent a single individual found all the way back in 1938 at the bottom of an old well at Sverresborg Castle near Trondheim in central Norway. Back then, we didn’t have the sophisticated genomic analysis tools that are available now, so there wasn’t much we could tell about the individual.

But, well, now we do have those tools. So a team led by genomicist Martin Ellegaard of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology decided to revisit the bones of the Well Man to see what secrets about his life may be locked within.

“This is the first time that a person described in these historical texts has actually been found,” Martin says. “There are a lot of these medieval and ancient remains all around Europe, and they’re increasingly being studied using genomic methods.”

Osteological research published in 2014 showed that the bones belonged to a man who was between the ages of 30 and 40 when he died. Martin and his colleagues undertook an intensive campaign that involved radiocarbon dating, gene-sequencing, and isotope analysis to get a more complete picture of the man’s identity.

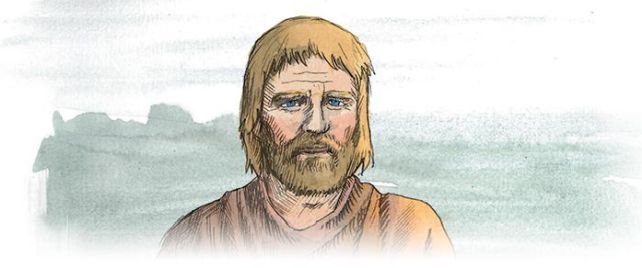

The radiocarbon dating showed that Well Man died around 900 years ago – consistent with the date of the 1197 CE invasion of Sverresborg Castle. We also know, thanks to the genomic analysis, that he likely had blond or light brown hair, and blue eyes.

Thanks to a comprehensive database of modern Norwegian genomes, the researchers were also able to figure out where the man was likely from – the southernmost Norwegian county, Vest-Agder, hundreds of kilometers from Trondheim.

“Most of the work that we do is reliant on having reference data,” says genomicist Ellegaard. “So the more ancient genomes that we sequence and the more modern individuals that we sequence, the better the analysis will be in the future.”

Isotope analysis is a tool that can help confirm radiocarbon dating, but also information about how and where a person has lived. Scientists extracted isotopes of carbon and nitrogen from Well Man’s bones, and linked the ratios to a diet rich in seafood.

We don’t know his name, or the manner of his death; he was dead before he was thrown into the well and rocks piled in on top of him, according to the saga. But it’s possible that he died during the invasion of Sverresborg Castle.

The event was a stealth attack carried out by the Roman Catholic enemies of King Sverre (known as Baglers, or Bagal, for the crosiers carried by bishops). While he wintered elsewhere, the Baglers invaded his castle in his absence.

“Thorstein Kugad accepted service with the Bagals, and went with them,” the saga reads. “The Bagals seized all the property in the castle, and then they burnt every building of it. They took a dead man and cast him into the well, and then filled it up with stones. Before they left the castle they called upon the townsmen to break down all the stone walls; and before they marched from the town they burnt all the King’s long-ships. After this they returned to the Uplands, well pleased with the booty they had gained in their journey.”

According to the saga, the Baglers spared the people within, leaving them nothing but their clothes – but fresh corpses don’t fall from the sky, and it’s plausible that the event wasn’t completely bloodless. The Well Man may even have been a Bagler himself, slain by the castle’s defenders.

“The text is not absolutely correct – what we have seen is that the reality is much more complex than the text,” explains archaeologist Anna Petersén of the Norwegian Institute of Cultural Heritage Research.

The research also demonstrates the power of a comprehensive genomic database, strong historical records, and how the two can be united to unveil the secrets of the past.

The research has been published in iScience.

[ad_2]