[ad_1]

Driving an ambulance or taxi as your job may provide some protection against Alzheimer’s, according to a new study that discovered these occupations have the lowest rates of death associated with the disease.

Researchers analyzed US death certificates for almost 9 million people who died during 2020–2022, linking occupational data across 443 professions with Alzheimer’s as a cause of death.

After adjusting for risk factors, the team from Harvard Medical School found a significantly lower proportion of Alzheimer’s-related deaths among individuals who drove taxis and ambulances for a significant part of their working lives, compared to those in other occupations and to the general population.

The study doesn’t prove that spending your work hours taking sick and injured people to the hospital or driving overly merry passengers around for holiday cheer lowers the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. But it does suggest a link to investigate further, potentially leading to ways to prevent the disease or slow its progress.

“The same part of the brain that’s involved in creating cognitive spatial maps –which we use to navigate the world around us – is also involved in the development of Alzheimer’s disease,” says public health researcher and physician Vishal Patel.

The small, seahorse-shaped part of our brains called the hippocampus is crucial for learning, memory, and spatial navigation, and one of the first areas to deteriorate in Alzheimer’s.

Previous research has shown hippocampus differences in London taxi drivers compared to the general population, so the team wanted to investigate further.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0GXv3mHs9AU

“We hypothesized that occupations… which demand real-time spatial and navigational processing, might be associated with a reduced burden of Alzheimer’s disease mortality compared with other occupations,” Patel says.

The national record of all death certificates in the US includes details about the underlying cause, the person’s sociodemographic information (such as age, sex, race, ethnicity, and education), and their usual occupation – the job they worked in for most of their life.

From deaths recorded over the three years from January 2020 to the end of 2022, the study team identified 8,972,221 individuals with occupational data, with a total of 348,328 people having Alzheimer’s listed as an underlying cause of death.

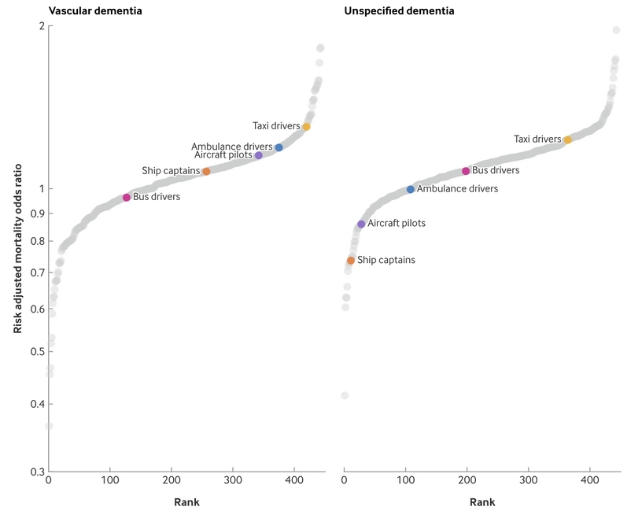

Along with taxi and ambulance drivers, the researchers analyzed bus drivers, aircraft pilots, and ship and boat captains – and grouped all other jobs from the 443 occupational groups as a general comparison category.

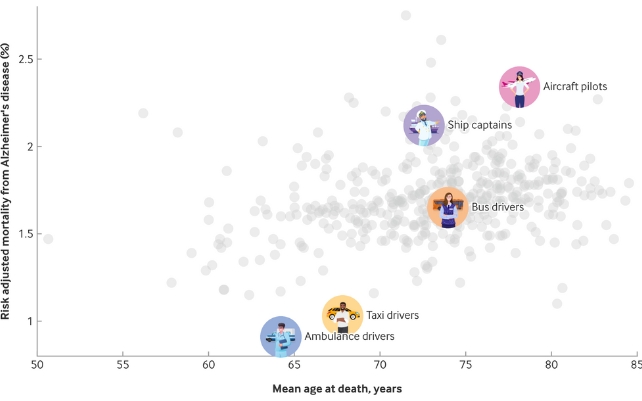

After adjusting for other factors like age at death, 1.03 percent of taxi driver deaths and 0.91 percent of ambulance driver deaths were attributed to Alzheimer’s disease. That’s significantly lower than the 1.69 percent prevalence in the broader population.

“Our results highlight the possibility that neurological changes in the hippocampus or elsewhere among taxi and ambulance drivers may account for the lower rates of Alzheimer’s disease,” says physician Anupam Jena.

Bus drivers had a 1.65 percent risk of dying from Alzheimer’s​​, while ship captains had a 2.12 percent risk and aircraft pilots showed 2.34 percent Alzheimer’s-related mortality.

Though tasks conducted in the duty of an occupation may have a role in slowing the disease’s progression, there could be other effects in play affecting the way results are interpreted.

“The age at death of taxi and ambulance drivers in this study was around 64-67 years of age, while for all other occupations this was 74 years of age,” University of Edinburgh neuroscientist Tara Spires-Jones points out in an expert reaction.

“The age of onset of Alzheimer’s is typically after 65 years old, meaning that the taxi and ambulance drivers might have gone on to develop Alzheimer’s if they lived longer,” Spires-Jones explains.

“Similarly, the proportion of women taxi and ambulance drivers was 10-22 percent whereas in all other occupations this was 48 percent. This is important because women are more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease than men.”

It’s also possible that people who are predisposed to Alzheimer’s disease may avoid memory-intensive jobs, and the study assumes ‘usual occupation’ represents most of a person’s working life, while some of us change jobs as frequently as we switch streaming services.

The team notes they only measured the rate of Alzheimer’s-related deaths, which may vary from disease frequency.

Future research could investigate whether the spatial cognitive tasks involved in driving taxis and ambulances directly impact Alzheimer’s and if any targeted activities can protect against the disease and its related mortality.

The authors write that they “view these findings not as conclusive, but as hypothesis generating.”

[ad_2]