By Katarzyna Ogrodnik-Fujcik

In December 1170, Thomas Becket, the archbishop of Canterbury sent a gift to Henry the Young King, the regent during Henry II’s absence from England, “three valuable destriers, of remarkable speed, elegant stature and beautiful appearance, which walked tall, lifting supple legs, flickering their ears and quivering their limbs, standing restlessly, clothed in flowered and multicoloured trappers…” They were to soften the young man’s heart and assure his goodwill. Thomas’ precarious position and his uncompromising stance made him vulnerable to his enemies. He desperately needed to mend fences with his former royal ward.

According to William Fitz Stephen, Becket’s biographer, Henry II was not the first to choose Lord Chancellor as his son’s tutor.

…magnates of the kingdom of England and of neighboring kingdoms placed their children in the chancellor’s service, and he grounded them in honest education and doctrine… The king himself, his lord, commended his son, the heir to the kingdom, to his training, and the chancellor kept him with him among the many nobles’ sons of similar age, and their appropriate attendants, masters and servants according to rank.

Young Henry was seven years old when he entrusted to Becket’s care in 1162, at the Easter court at Falaise. At the behest of the king, the then-chancellor took his young ward to England in April. He was to call the Great Council in the king’s name and prepare the prince for his recognition by the bishops and magnates of the realm. It was in London, where young Henry was presented with the petition that his freshly-assigned tutor should be appointed as archbishop and asked to give formal consent to it.

On 3 June he witnessed Becket’s consecration at Canterbury. What he must have witnessed too was his tutor’s almost day-to-day transformation from the worldly chancellor into a monk exercising both his flesh and soul. With “a hairshirt of the roughest kind, which reached to his knees and swarmed with vermin” and with the mortification “of his flesh with the sparest diet” came other changes in the former chancellor:

… the glorious Archbishop Thomas, contrary to the expectation of the king and everyone else, so utterly abandoned the world and so suddenly experienced that conversion, which is God’s handiwork, that all men marvelled thereat.

The one who marvelled most must have been Henry II himself. What his eldest son thought about Becket’s conversion, we will never learn. But this sudden day-to-day change in his worldly tutor must have taken him by surprise. To make things worse, the Archbishop chose to oppose young Henry’s father in all matters, both of lesser and crucial importance. To show his ever-growing displeasure towards his former chancellor and friend, Henry II had his son removed from Becket’s household.

But the short time spent in Becket’s tutelage (c. May 1162- October 1163) proved to be enough to leave the boy with his head full of visions of splendor, visions quite different from those nourished by his father, the king. Those who regard the Young King as a ‘charming, vain, idle spendthrift’ (Warren) should look for the origins of his taste for glamour, luxury and greatness underneath the roof of his tutor, Thomas Becket. As Professor Matthew Strickland points out, “the experience must have made a profound impression upon the boy, and not only the splendor of the household itself or the chancellor’s worldly ways, but also Becket’s own aspiring to perform a model knightly prowess and valor.”

In 1159, Young Henry, aged four, had seen Becket leaving Poitiers at the head of seven hundred knights in the course of Henry II’s Toulouse campaign. While accompanying the chancellor to Normandy in 1161, he may have seen the latter defeat the French knight Enguerrand de Trie in single combat. Finally, being Becket’s ward he had a chance to admire his tutor’s military household and see for himself, the chancellor’s knights ‘in all the army of the king of England… always first, always the most daring, always performed excellently’. Henry’s later displays of largesse and greatness, his prowess on the tournament field, and his own splendid household may all be a consequence of his stay in Becket’s tutelage.

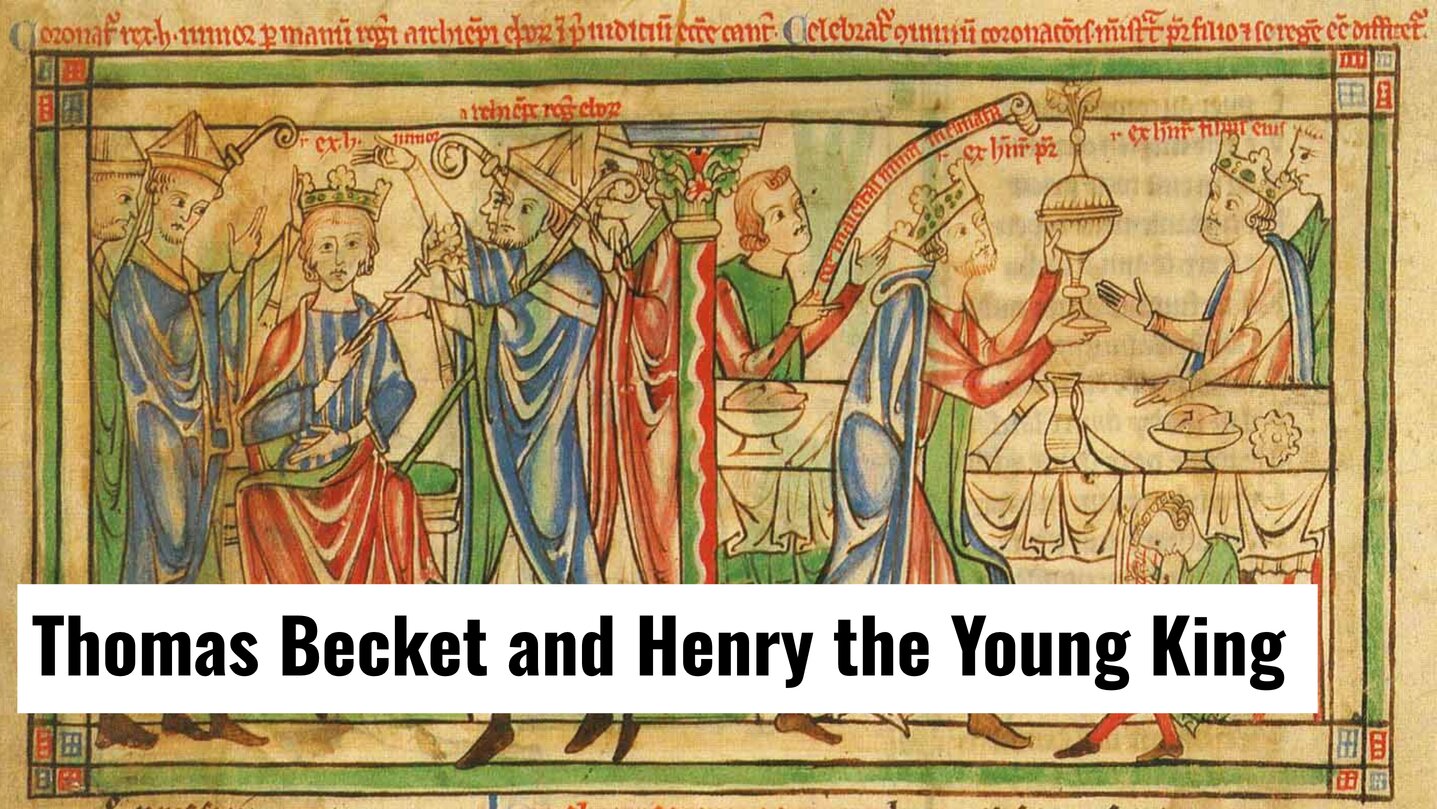

Young Henry was removed from Becket’s charge in October 1163, after the council at Westminster, although the first signs of his father’s growing displeasure with the archbishop were observed prior to the event. The conflict postponed plans for Henry’s coronation. When it eventually took place, in June 1170, it was a blow to Becket’s position. The ceremony was performed by the Archbishop of York instead of the Archbishop of Canterbury, a departure from the ancient tradition Becket could not swallow. He protested before the event and afterwards, but to no avail. Ironically, it led to his reconciliation with the king. They came to terms at Freteval. Becket’s lands were restored and he was allowed to return to England, but the matter itself remained unsolved.

Upon his return Becket refused to lift the excommunication of the bishops involved in the coronation of the Young King. The latter, in his father’s absence was a regent in England. A writ issued by Henry II around 30 September 1170 survives. In it he instructed his son about Becket:

Henry, king of England, to his son Henry, the king, greeting. Be it known to you that Thomas, archbishop of Canterbury, has made peace with me according to my will. I therefore command that he and his men shall have peace. You are to ensure that the archbishop and all his men, who left England for his sake, shall enjoy their possesions in peace and honour, as they held them three months before the archbishop withdrew from England. Moreover, you shall cause the senior and more important knights to the honour of Saltwood to appear before you, and by their oath you shall cause recognition to be made of what is there held in fee from the archbishop of Canterbury, and what this recognition shall declare to be within the fief of the archbishop you shall cause him to have. ~ Witnessed by Rotrou, archbishop of Rouen, at Chinon

Thomas tried to reach the Young King several times. He sent envoys to his court. Herbert of Bosham, John of Salisbury, Richard, prior of Dover and the abbot of St Alban’s all spoke in his name but the general mood in the country and the young king’s advisors prevailed. Thomas wanted to assure young Henry that he never opposed the idea of his coronation itself, but merely the fact that it was performed by the Archbishop of York instead of himself. He was convinced that given a chance they could have mended their fences. All they needed to do was to meet face to face. Unfortunately, he never got the chance. The former guardian and his former ward did not meet again.

If we are to believe William FitzStephen, young Henry was shaken by Thomas’ violent end and grieved bitterly. Although he was also relieved that none of his own knights had been involved. Three years later, when he rebelled against his father, he and his followers made good use of Becket’s martyrdom for propaganda purposes. Becket’s death was to be the main cause of the rift between the father and the son and thus justified the latter’s actions. But in the immediate aftermath of the event nothing indicated that he held his father responsible for it.

Katarzyna Ogrodnik-Fujcik is a teacher, amateur historian and freelance writer. She works with different magazines and websites on Polish and European history. She runs a blog dedicated to Henry the Young King.

Top Image: Left: Coronation of Henry the Young King by the Archbishop Roger of York (14 June 1170); Right: Henry II serves his son at the coronation feast. – British Library Loan MS 88