At the Malaysia International Halal Showcase last September, an unlikely sight caught the attention of many attendees.

Nestled among the booths from Muslim-majority countries such as Indonesia and Kuwait, a kiosk representing pork-loving, hard-drinking South Korea beckoned visitors to check out halal products ranging from seaweed laver to sanitary pads.

“The halal food market is a blue ocean with great potential for growth,” Lee Yong Jik, the head of the food export division at South Korea’s Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs, told Al Jazeera.

After taking the worlds of film, TV and pop music by storm, South Korea is setting its sights on the global halal industry, which caters to the dietary rules and lifestyle requirements of some 1.8 billion Muslims around the world.

Halal is not easily associated with traditionally homogenous South Korea, where the Muslim community is estimated to number fewer than 200,000 people, or less than 0.4 percent of the population.

But surging demand for Korean cuisine and snacks in Southeast Asia, where Korean pop culture has a devoted and growing fanbase, has turned Korean exporters onto a potentially lucrative opportunity.

Muslims’ spending on halal food alone reached $1.27 trillion in 2021 and is projected to reach $1.67 trillion by 2025, according to research firm DinarStandard.

South Korea’s government has been keen to encourage businesses to capitalise on the trend, providing assistance ranging from food ingredient analysis to subsidies for certification fees and promotional events to connect buyers and suppliers.

In 2015, then-President Park Geun-hye signed an agreement with the United Arab Emirates to promote businesses in new markets, including halal food.

In Daegu, South Korea’s fourth-largest city, local authorities have spearheaded a “Halal Food Activation Project” aimed at increasing the number of halal-certified companies in the city tenfold and tripling exports to $200m by 2028.

Daegu Mayor Hong Joon-pyo recently described the halal market as an opportunity that “cannot be ignored”.

Lotte Foods, CJ CheilJedang, Daesang and Nongshim are among the Korean food giants to have rolled out halal-certified products from kimchi to rice cakes.

Last year, South Korea began exporting halal Korean native beef, known as hanwoo, for the first time after receiving the go-ahead from Islamic affairs officials in Malaysia.

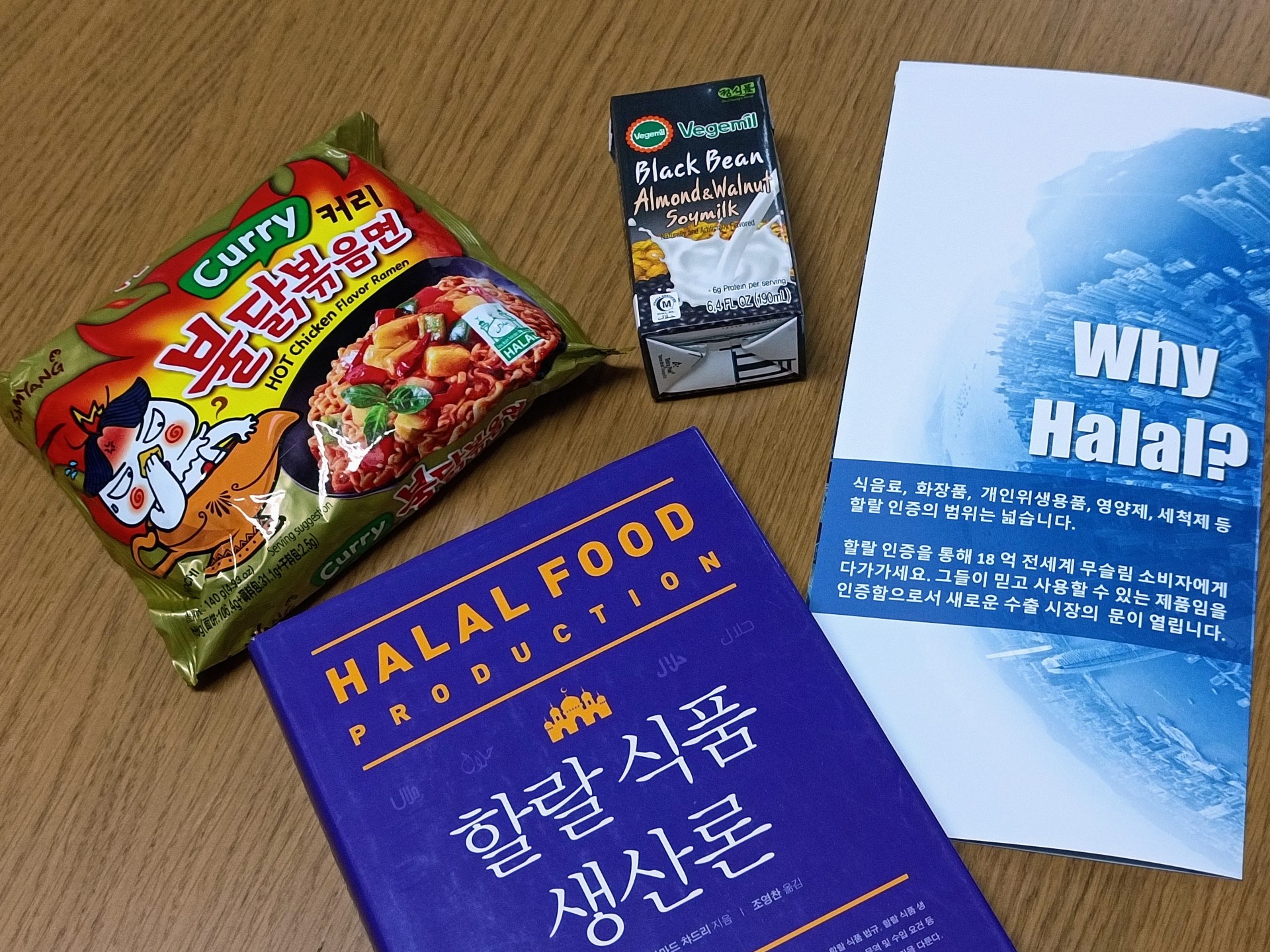

Samyang Foods, one of South Korea’s leading food manufacturers, exports halal products to 78 countries, including its wildly popular “Buldak Ramen” instant noodles.

Samyang’s sales of halal products reached $200m in 2022, accounting for about 45 percent of total exports. Sales in 2023 were expected to reach about $270m.

Samyang has “consistently recognised the importance of the Muslim market” and has been actively working to promote “K-food” globally, a company spokesperson told Al Jazeera.

Apart from the food industry, players in the so-called “K-beauty” sector have also cashed in on the trend.

Cosmetics manufacturer Cosmax, which has its headquarters in Seoul, has been producing halal products at its facilities in Indonesia since 2016.

Despite the growing market, gaining halal certification can seem daunting for many businesses, especially smaller firms.

“The first step is to determine if your product is halal and if it is, then assess whether you actually need halal certification,” Saifullah Jo, chairman of the Korea Halal Association (KOHAS), told Al Jazeera.

A South Korean national who converted to Islam, Jo founded an Islamic consultancy firm for Korean companies and has translated a book about halal into Korean.

“Just because a company requests certification, doesn’t mean we will grant it. Some people come to us seeking certification for things that may technically be certifiable but it’s not always practical,” said Jo, whose organisation is one of South Korea’s four halal certification bodies.

“We need to consider the audience and the genuine necessity for certification.”

While alcohol, blood, pork and animals not properly slaughtered in the name of God, and meat from animals that died before slaughter, are considered haram, or prohibited, even seemingly innocuous items like rice and mineral water can be candidates for halal certification.

“The complexities arise in the production processes. For example, when rice is separated from husks in the milling process, the machinery involved may utilise lubrication and some oils may contain animal-derived ingredients,” Jo said.

“This causes cross-contamination and presents a challenge for ensuring the final product is halal-compliant.”

To make matters more complicated, Indonesia, home to the world’s largest Muslim population, last year announced that food companies would from October be required to obtain halal certification within the country.

In November, the South Korean and Indonesian governments reached an agreement to exempt agricultural and food products from certification in the Southeast Asian country so long as they have received the halal label from two of South Korea’s certifiers.

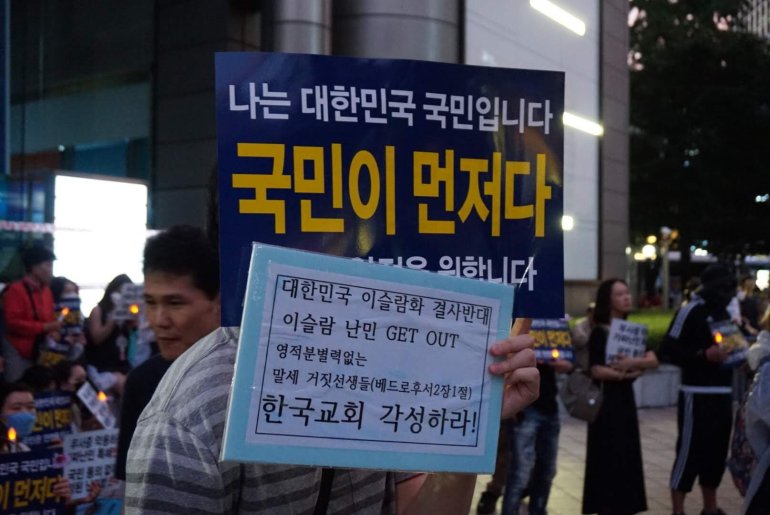

While South Korea has made no secret of its ambitions to forge business connections with the Muslim world, social attitudes towards Muslim people and Islamic culture are often not so friendly.

“Muslims in South Korea are viewed at best with apathy and, at worst, with fear,” Farrah Sheikh, an assistant professor at Keimyung University who specialises in Islam in South Korea, told Al Jazeera.

Sheikh said some Koreans view halal products as a conduit for Islam to “invade” Korean society.

In Daegu, where officials are aggressively pursuing the Muslim market, plans to construct a small mosque have encountered fierce opposition from residents and conservative Christian groups.

In August last year, rapporteurs of the United Nations Human Rights Council expressed “serious concern” to the South Korean government over its alleged failure to address the campaign against the mosque, which included the display of pig heads outside the construction site and banners describing Islam as “an evil religion that kills people”.

After the government began promoting the halal industry in 2015, several Christian groups began warning about the potential “Islamification” of South Korea, an alleged influx of Muslims and concerns about security risks associated with halal food, leading the government to issue an explanatory document to dispel misinformation and rumours.

In 2016, the proposed construction of an industrial zone for the production of halal-certified products in the western city of Iksan fell through due to opposition from Christian groups.

That same year, a brand of potato chip made in Malaysia attracted controversy over halal certification on its packaging, which was later removed without explanation.

In 2018, South Korea witnessed a wave of protests against the arrival of several hundred Muslim asylum seekers from Yemen. During the same year, plans for a prayer room at the Winter Olympic Games were cancelled, following vehement protests by anti-Muslim campaigners.

For Muslims actually living in South Korea, halal products can be difficult to find.

While there are restaurants offering halal food, they are primarily clustered in Seoul and other large cities with substantial Muslim communities.

With little in the way of halal products available on supermarket shelves, some Muslim residents have resorted to re-importing halal-certified “made in Korea” instant noodles for their consumption.

Asked about the lack of halal products in South Korea, Samyang Foods said there was insufficient domestic demand to support a market at present.

“However, as the number of Muslim visitors and residents in Korea increases, interest in halal products is growing. Samyang Food is also reviewing the marketability of selling halal products in the Korean market to make it more convenient for domestic Muslim consumers to purchase halal products,” a spokesperson said.

Sheikh, the Keimyung University professor, said Korean companies could not be blamed for wanting to cash in on a lucrative market.

“However, when we see Korean attitudes towards Muslim refugees, or as we have seen in Daegu, we have a clear discrepancy and a big social problem,” he said, adding that South Korea must improve its attitude towards Muslims if it wants to better target markets overseas.

Saifullah Jo of KOHAS said he sees a bright future for Korea’s halal industry despite the challenges.

“Looking at it from the Korean industry’s standpoint, we are aware of the potential, and we should move swiftly. One of Korea’s key strengths is its ability to adapt rapidly,” he said, adding that a growing halal market could promote tolerance and understanding.

“Despite some negative minds, we are thinking positively about going into this new market, and Koreans are learning as well. It helps us open up culturally.”