The ancient-looking PA system was not meant to handle the immensity of sound produced by famed Nile Delta folk music ensemble El Tanbura as they warmed up for a show on the streets of Ismailia on a warm summer night in 2019 – one of several shows in the Suez Canal’s major towns marking 30 years since El Tanbura’s founding.

The volume and distortion made for a mash-up of the traditional music of the Delta with the signature sonic footprint of mahraganat, the contemporary urban youth music that rose from outdoor weddings in working-class neighbourhoods to take Egypt and much of the Middle East by storm during the last decade.

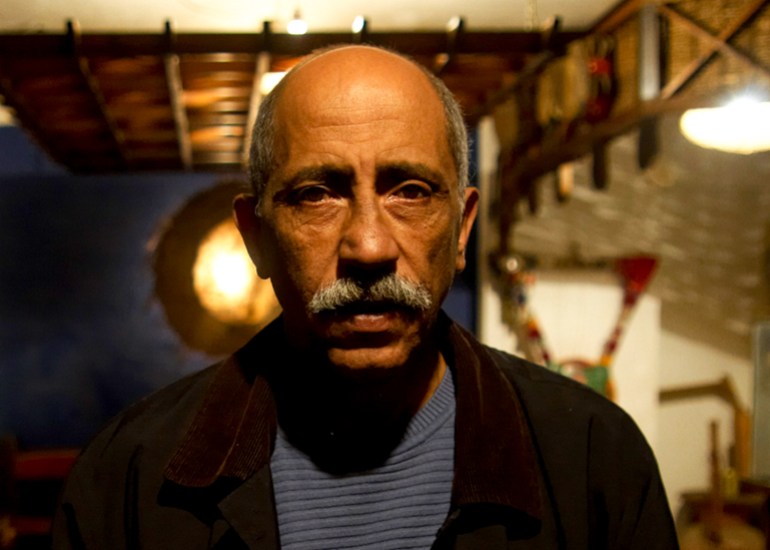

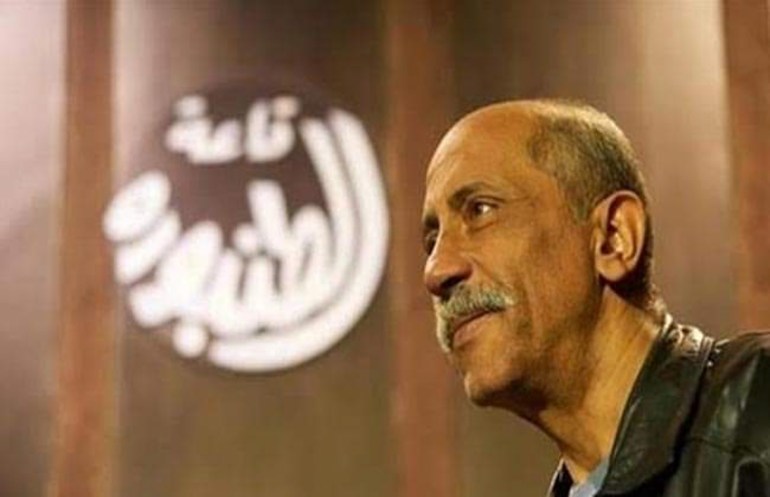

Overseeing the warmup with his characteristic smile was legendary musician Zakaria Ibrahim – El Rayes (a ship captain or a boss in general), the “godfather of popular art”, the “Pyramid of popular culture” – who passed away in Cairo on February 12 at the age of 72.

Zakaria founded El Tanbura in 1988 after struggling for nearly a decade to find players of the simsimiyya, one of the world’s oldest instruments. Sometimes called a box lyre, the simsimiyya is the smaller cousin of the tanbura, a five-stringed lap harp with roots stretching from ancient Egypt – it appears on art going back to the Middle Kingdom, about 2000 BCE – to India.

Rayes Zakaria’s work to revive interest in ancient instruments made him a giant of Egyptian, African and world music.

He was also a revolutionary artist – centring his life and art around using music to encourage if not enable change in Egyptian society and to support the people after the revolutionary moment inevitably ends.

He cared deeply about his songs, and about the history and culture behind each one, to the point where he was known to lose track of time and space.

But that was precisely the point of most of the music he helped create as the founder and singular force behind the El Mastaba Center for the Preservation of Egyptian Folk Music, Egypt’s – and likely the Arab world’s – most important institution dedicated to traditional music.

Zakaria Ibrahim’s musical roots

Zakaria was born in Port Said in 1952, the same year as the Egyptian revolution, and came of age in an atmosphere of resistance and patriotism between the 1956 war against Israel, the United Kingdom and France and the 1967 war.

During this time, the shaabi (popular, working class) music of Port Said and the Canal became famed across Egypt and the Arab World as the music of resistance, the lyrics and propulsive rhythms matching the spirit of resistance against British and then Israeli invasion and colonialism.

Port Said was in the thrall of dama during this time – a combination of party music and transcendental experience that combined popular love songs and Sufi music from different traditions in the Nile Delta and Canal zone and used the simsimiyya to produce the sound that captivated Port Said.

In the three years following 1967, Egypt fought the War of Attrition with Israel and the songs of the simsimiyya travelled across Egypt, taken there by the people displaced from the Canal zone by the war to serve as a reminder of their hometowns.

Zakaria moved to Cairo in the early 1970s to attend university, just as Egypt moved from the Arab nationalist politics of President Gamal Abdel Nasser to the more neoliberal and pro-Western policies of his successor, Anwar Sadat.

He became deeply involved in the left-wing student movement, ultimately serving a short stint in prison because of his activities.

At the same time, the music of the simsimiyya, which had been so deeply ingrained in the culture of Port Said and the broader Delta, became increasingly commercialised.

“Instead of being the way we were before, singing and gathering in the streets all together then leaving together, now, there is a situation where the one who is coming to attend has to pay the one who sings,” Zakaria once lamented, criticising what he saw as the commodification of the music of the people.

Meanwhile, the music of the zar, and particularly the rango, had all but become extinct except as a tourist curiosity.

When he returned home at the turn of the 1980s, Zakaria found his mission: not only to salvage or even conserve the music he loved but to bring together as many of the old practitioners as he could find to revive it and, with it, the spirit of the community, as well as resistance.

“Zakaria was an African Alan Lomax,” Moroccan-Italian musician and filmmaker Reda Zine said, referring to the famed ethnomusicologist who did so much to preserve traditional music.

“He was trying to redraw the ancient caravan routes, to highlight the healing, just like the Gnawa in Morocco,” Zine explained, referring to the North African country’s Sufi music.

To be sure, from the first moment Zakaria listened to Gnawa at El Mastaba, he could hear the similarities in mood, in the strings and songs from one end of North Africa to the other.

“Zakaria saw the connections between the healing power of Sufi music… the way others looked at tarab [virtuosic art music],” Zine explained.

“And he saw how the Moroccan government had finally come to support Gnawa and its culture, and he wanted to achieve the same for the spiritually grounded folk music in Egypt.”

The simsimiyya, the tanbura and the “rango” – a small wooden xylophone that together with the tanbura has long been the primary instrument of various types of ritual gatherings known as zar ceremonies – have a spiritual past, the source and route of which varies depending on who’s telling it.

Their modern origins centre around the conquest of modern-day Sudan in 1820 by Egypt’s Muhammad Ali and the participation, as slaves and free people, of increasing numbers of Sudanese, Nubians, Ethiopians and other East Africans in the burgeoning “Egyptian” army, as well as in cotton cultivation and trade more broadly.

With the establishment of Port Said in 1859 and the abolition of the slave trade at the end of the 19th century, major Egyptian cities right up to the Mediterranean saw a marked increase in sub-Saharan communities, and eventually neighbourhoods and quarters.

Their cultural, religious and musical practice intersected and embedded with local practices to produce various forms of modern Egyptian folk music, most of which are rooted at least partly in the Sufi and East African traditions that define groups like El Tanbura, Rango and other ensembles created or sponsored by El Mastaba.

Revolution, evolution

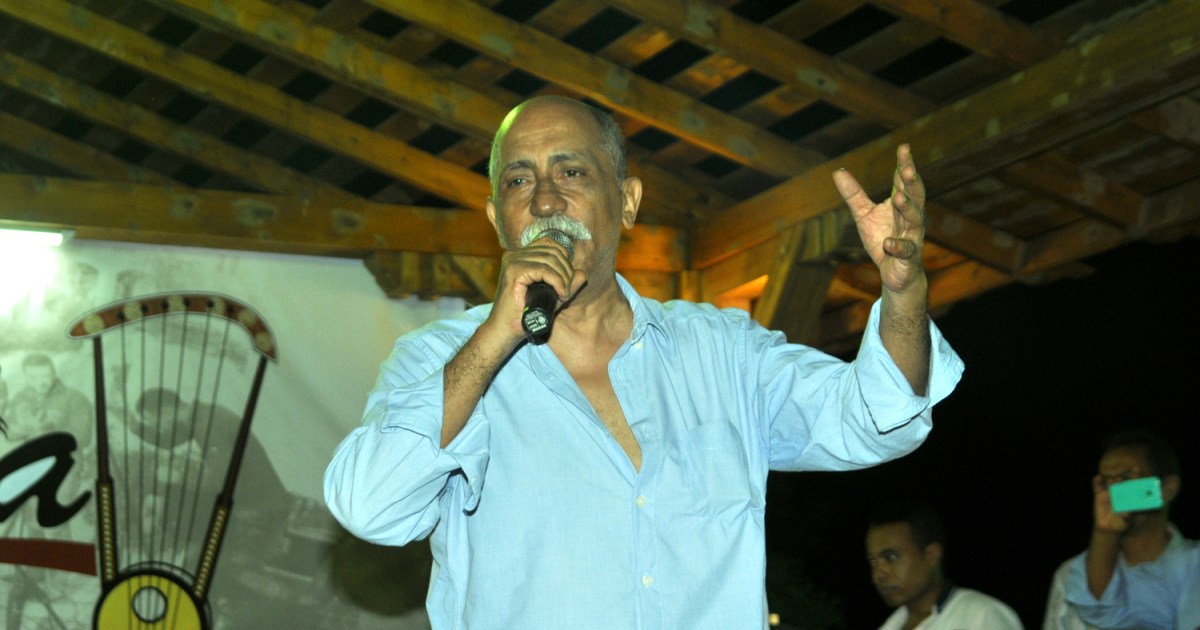

One of the most powerful moments of the 18-day Egyptian Arab Spring uprising of 2011 was when El Tanbura marched – danced, really – into Tahrir Square, the symbolic heart of the protest movement.

El Tanbura sang revolutionary songs that were sung first against Israel in 1956 and 1967, underscoring both the stakes of the protests and whose side the politically grounded artists were on.

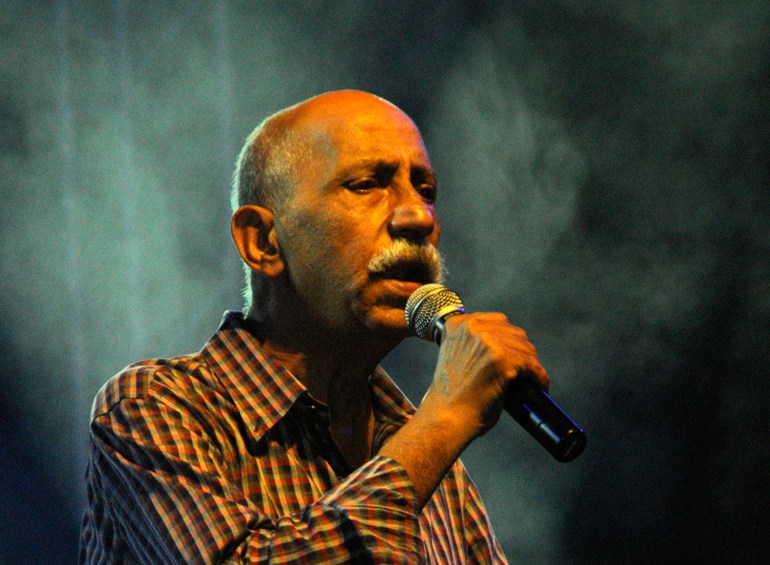

Six months on from the start of the revolution on January 25, El Tanbura was at London’s Barbican to perform with other musicians who played in Tahrir Square. This began a series of tours that would take them across the Arab world, Europe and Asia, including major festival stages like Glastonbury and Roskilde.

Listening to Zakaria describe his music, never mind sing and dance to it on any stage, it became clear that what made El Tanbura so powerful was what makes all the best Sufi music so popular: the mix of sacred and profane, spiritual and earthy, in the service of music that forces even the most reluctant listener to join in and dance.

The simsimiyya, which had been the “pulse of the people” as far back as 1956, once again helped drive revolutionaries forward, not just for politics, but as Zakaria liked to say, “for love … It’s the Sufi feelings, people submerged in love, together.”

For anyone who attended a performance of El Tanbura, Rango, or the other bands of El Mastaba, such as NubaNour and Bedouin Jerry Can, that idea of being submerged – or as Zakaria would describe it, of simply letting go and flying – was a regular occurrence, whether in the Canal cities or at their Cairo base, the El-Dammah Theatre in Abdeen.

On any given Wednesday or Saturday night, during their regular shows, the groups sang and danced to what can best be described as party music with a spiritual core, which also created the very real material Zakaria needed to get his musicians respect, credit and income for their art.

What Zakaria understood is that when you are dealing with heritage music, it is not just about conserving the past, it is about composing the future. Sometimes this is the only revolutionary act still possible, especially after Egypt’s counter-revolutionary coup of 2013 made dancing into the square with simsimiyyas and dafs raised overheads, singing “Get up and take your freedom”, all but impossible.

Two days after the 2019 show in Ismailia, Zakaria stood on the shore of the Mediterranean at El Tanbura’s home base in Port Said, after another performance by the group in front of their most ardent fans.

His face glowed slightly in the moonlight, illuminating not just contentment but the stress of running an independent organisation with a history of resistance music as Egypt’s counter-revolutionary era dragged on.

When I asked him why, at nearly 70 years old, he continued to work at the frenetic pace the groups and the music demanded, he responded instantly: “Mark, I’ll play till I die.”

But he stopped performing weeks before his passing, in protest against the destruction wrought by Israel’s war on Gaza and possibly of the Egyptian government’s response.

Zakaria, whose friends called him the “ambassador of joy”, spent his final weeks not playing the music he did so much to conserve, and which brought him and so many others joy.

Mamdouh Elkady, executive manager at El Mastaba and Zakaria’s assistant for more than 30 years, summed up the intensity of the sense of loss from his passing.

“With the death of Zakaria, we lost the central pillar of the tent that shaded us with his compassion and love for everyone working in the traditional folk music system,” Elkady said.

“But given all the problems the country, region and world face today, we have to continue his vision. The time for resistance as well as joy, revolution as well as togetherness, has returned.”

That’s a message Zakaria Ibrahim, impresario, organic intellectual and revolutionary, would have been able to sing and dance to straight through till dawn.