Cervical cancer is the only cancer that is vaccine-preventable and curable, but the United States is lagging in its efforts to meet the World Health Organization’s 2030 targets to effectively eliminate the disease.

A mix of low vaccination uptake — just 61.7% of U.S. teenage girls were up to date on their HPV vaccine doses in 2022, according to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention survey — combined with health equity issues have hobbled U.S. efforts to end the disease.

The combination can be deadly: Though cervical cancer is now preventable and treatable, roughly 11,500 new cases are reported in the U.S. each year and roughly 4,000 women die of the disease, according to CDC data.

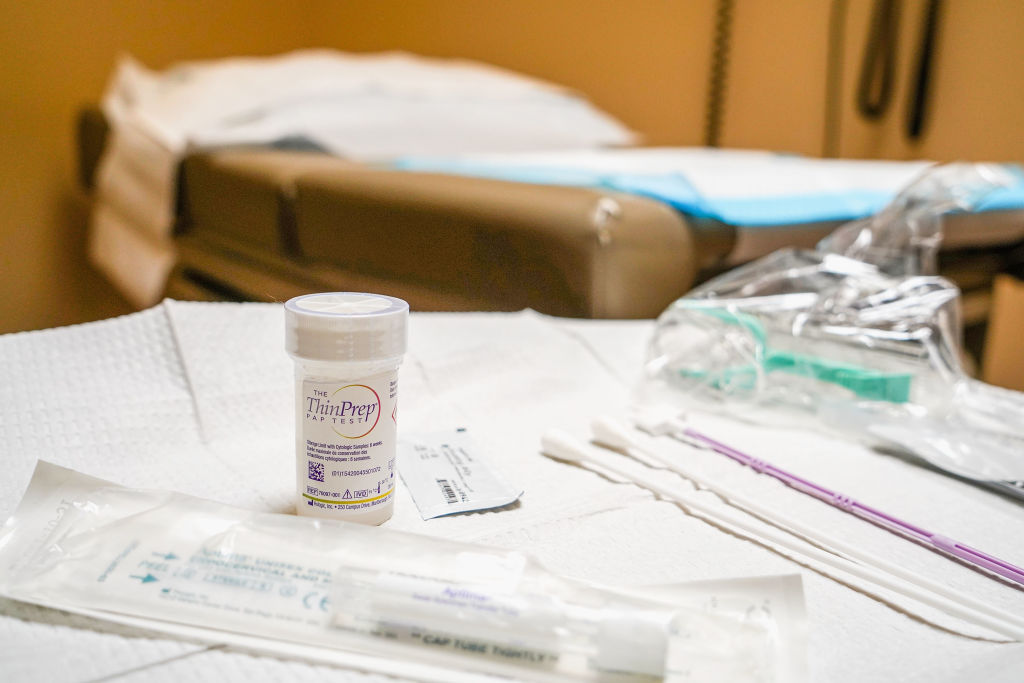

Alarmed by the increase, the Biden administration last week announced a handful of measures aimed at fighting the disease, including a new initiative to lower rates of cervical cancer by allowing for Americans to test for human papillomavirus, or HPV, which causes most cervical cancer, at home.

The new program, called the Self-collection for HPV Testing to Improve Cervical Cancer Prevention, will launch in the second quarter of this year.

The initiative will be a clinical trial network to gather data on the self-collection method of HPV, to prevent cervical cancer.

If the method is determined viable, it could dramatically increase uptake of cervical cancer screening.

Heather White, executive director of TogetHER for Health, an organization that works to eliminate cervical cancer globally, said the Biden administration’s self-sampling initiative could be “a real game changer” for U.S. efforts to stem HPV, because it’ll help get more screenings to women in rural areas and those who may otherwise have issues accessing the health care system.

“That’s a major milestone to be able to turn the regulatory corner,” she said of potential approval of the HPV self-sampling kits. “And I think that’s really where you’ll start to see a sea change in terms of screening uptake.”

Equity issues

Health equity and vaccine access issues have plagued the HPV vaccination effort in the U.S., so much so that cervical cancer incidence and deaths are on the rise among low-income women in rural areas, according to a new study led by researchers from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, published in the International Journal of Cancer.

The rise in cases comes despite a longtime solution: In 2006, the Food and Drug Administration approved Gardasil, an HPV vaccine developed by Merck and Co. Inc., and CDC advisers recommended the shot in 2007.

The shot has proven highly effective: A study published last week in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute found no cervical cancer cases detected in women born between 1988 and 1996 who received the HPV vaccine when they were adolescents.

In the decades following the introduction of cervical cancer screening tools in the U.S., cancer rates decreased. But these interventions have occurred less frequently in rural areas of the country lacking access to care, according to the MD Anderson study. This is hitting non-Hispanic white women in low-income counties particularly hard, as this group has seen a 4.4 percent increase in cervical cancer occurrences since 2007.

Black women saw the largest increase in cervical cancer deaths, at 2.9% annually since 2013, even though cancer incidence in this group is declining.

White, of TogetHER for Health, said her home state of Alabama has experienced the disparity firsthand.

The state lacks health care providers in many areas and women might have to wait months to get an appointment for a screening. Couple that with a lack of awareness about the disease and many women end up skipping appointments.

Alabama’s HPV vaccination rates track slightly lower than national averages so the state’s public health department recently launched a 10-year plan to up vaccination rates to 80% by 2033.

Reaching vaccine-hesitant Alabamans will require many of the tools state health departments utilized during the COVID-19 pandemic: health education and meeting people where they are.

“We’ve had a challenge, certainly in this country for many years around misinformation, disinformation, related to the HPV vaccine. And I think of course that is compounded by vaccine hesitancy, which has certainly been exacerbated by COVID,” White said.

Capitol Hill push

Congress, meanwhile, is due to reauthorize a key cancer detection program that helps low-income Americans gain access to timely breast and cervical cancer screening, diagnostic and treatment services.

Sens. Tammy Baldwin, D-Wis., and Susan Collins, R-Maine, introduced a bill to reauthorize the cervical cancer detection program for fiscal years 2024 to 2028. The measure, as approved by the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee last month would fund the program at $275 million per year, an increase from current levels of $235.5 million a year.

A Baldwin staffer said the two senators, who are both lead appropriators, are trying to attach that measure to an upcoming spending bill. But nothing is set yet.

The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program was first authorized by Congress in 1990.

Global efforts

The United States’ efforts mirror international ones: The World Health Organization aims to eliminate cervical cancer globally in the next century. It has asked participating countries to set ambitious targets to meet by 2030.

Among them: All countries must maintain an incidence rate of or below 4 cases per 100,0000 women, which means vaccinating 90% of young girls with the HPV vaccine by age 15, screening 70% of adult women by age 35 to 45 and treating 90% of women with pre-cancer.

Those efforts, too, are lagging. Cervical cancer is the fourth-most common cancer globally, with an estimated 604,000 cases reported every year. The disease is typically caused by Human Papillomavirus, or HPV, a relatively common sexually transmitted virus.

“At the end of 2022 only about 21% of women globally had coverage with a single dose of the HPV vaccine,” said Pavani Ram, chief of child health and immunization at the U.S. Agency for International Development, at an event at the White House last week. “That’s a long way away from the 2030 target of 90%-plus that we need to be at in order to achieve cervical cancer elimination goals.”

©2024 CQ-Roll Call, Inc., All Rights Reserved. Visit cqrollcall.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.