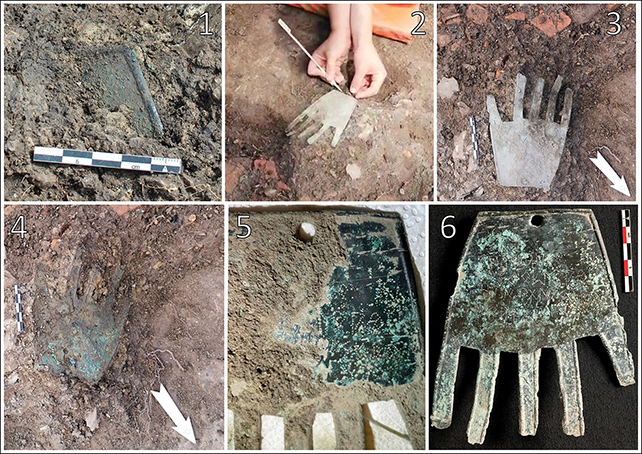

Researchers have come across a wonderfully intriguing find in the north of Spain: a bronze hand dating back some 2,000 years, all the way back to the Iron Age, with four lines of strange symbols inscribed across its top.

A new study suggests that this ancient epigraph is related to ancient Paleohispanic languages, and may have been part of the language that has developed into Basque in modern day Spain.

The area is known to have been populated by a tribe called the Vascones around the time the hand would’ve been made – a tribe that left behind very little in the way of writing samples, which has led to the assumption that they were pre-literate. This hand shows that might not be the case.

“Detailed linguistic analysis suggests that the script represents a graphic subsystem of Palaeohispanic that shares its roots with the modern Basque language and constitutes the first example of Vasconic epigraphy,” write the researchers in their published paper.

The script’s orientation, along with the position of a small hole in the object and the location of its discovery suggest it may have been hung by the entrance of a building.

This lettering was inscribed using the sgraffito technique to create the lines, which was then followed by bigger punched dots. It’s not clear what instruments were used, but the researchers think a sharp iron tool like a burin could’ve been one of them.

Based on words that could be identified and comparisons with other artifacts, the researchers think the language comprises a “distinct sub-system”. While it’s not possible to fully translate the text, the researchers did find some interesting parallels with modern Basque.

One of the key links the researchers make is between the first word on the hand, sorioneku, and the Basque word zorioneko, which means of good fortune. That points to both the meaning of the hand’s message and connections to Basque.

“The text inscribed on this artifact, which was found at the entrance of a domestic building, is interpreted as apotropaic, a token entreating good fortune,” write the researchers.

It’s possible that the hand had some kind of ritual or cultural significance, according to the researchers. Ancient Iberians were said to have cut off the right hands of their captives, for example – though in spite of being a right hand the use of the symbol seems more benign.

Several Iron Age artefacts that depict the back of an open right hand have been discovered in the Vasconic and Iberian areas, and a more lifelike artifact from a similar time period found in Zafar (Yemen) also bears an interesting resemblance.

The team says that variations in letter size and some inconsistencies in the strokes of the letters suggest a rather careless and unplanned approach to the writing. Additionally, bronze is a common material in the area, so the researchers think it could have been crafted at the site where it was found.

Research continues into the so-called Hand of Irulegi, named after the site it was found at, and what it can tell us about the Vascones – specifically in terms of a written language that existed before the Romans arrived.

“The new inscription presented here provides support for a growing awareness that the ancient Vascones knew and made use of writing, at least to a degree,” write the researchers.

The research has been published in Antiquity.