I bet there are still some people among you who still don’t think bases on the Moon and trips to Mars are things we just might experience during our lifetimes. But you only have to look at the intense prep work the world’s space agencies and private companies are conducting, and at the fortunes they are spending, to realize that is indeed what will happen.

The DSN is made up of three antenna complexes located in Goldstone, California; Madrid, Spain; and Canberra, Australia. They are used for communication purposes with most of the human hardware presently in space, but more specifically with the ones really far out, like the Voyager spacecraft.

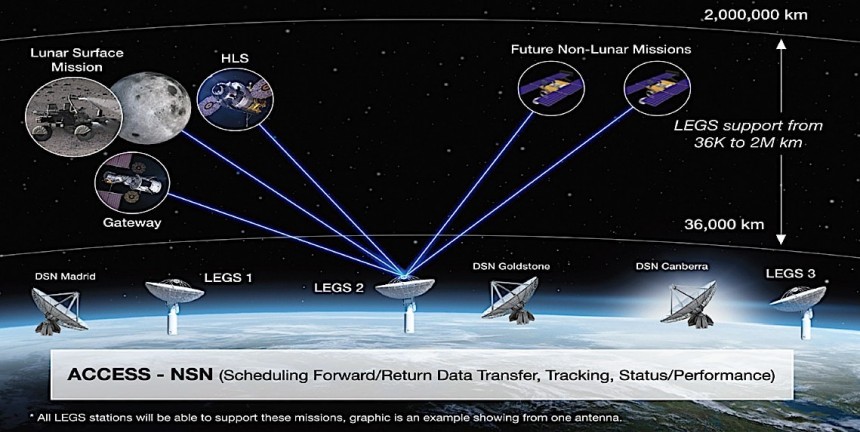

The NSN, on the other hand, was built to cover distances anywhere from near Earth to 1.2 million miles (1.93 million km) away, meaning it reaches the Moon, but also the Sun-Earth Lagrange points 1 and 2.

L2 is where the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) was placed and, together with L1, it is a region of space where the responsibilities of the two communication networks overlap.

The NSN network comprises a series of ground stations spread around the world, but it will soon get a major boost in power thanks to the arrival of something called LEGS. That’s an acronym for Lunar Exploration Ground Sites, which in turn represent a series of 66-foot antenna dishes that will be deployed in key locations around the world.

The first three will be up and running later this decade, and they will be located in New Mexico, South Africa, and Australia. The countries were chosen thanks to the fact they ensure an uninterrupted line of sight with the Moon, because as the satellite sets in one place, it rises in another.

The American continent-based antenna will be located at the NASA White Sands Complex in Las Cruces, while the South African one will be constructed in Matjiesfontein, near Cape Town – a choice that honors South Africa’s involvement in the Apollo program with its ground tracking station. The Australian site for LEGS has not been selected yet.

All LEGS will be incorporated into the NSN in a bid to ease the workload on the Deep Space Network, which will be free to handle communications with the spacecraft operating very far away from our world.

For the first Artemis mission, which concluded uncrewed in 2022, NASA used both the DSN and NSS to talk to the Orion spacecraft. The same thing will happen with Artemis II, but from Artemis III onward, the LEGS antennas should kick into gear.

That means the new system will be responsible for coordinating not only the first Moon landing but also the start of operations for the Gateway space station, the deployment of the SpaceX (and later Blue Origin) human landing system, and the adventures of the Lunar Terrain Vehicle (LTV).

The way the LEGS antennas are supposed to work is pretty simple. Antennas will pick up radio frequency signals that contain encoded data coming from satellites and spacecraft in lunar orbit, or from some other hardware on the surface.

Once received, the data will be distributed to operators around the world, who will have to decide what to do with the info and what to instruct the Moon hardware to do next.

All the first three antennas of the system will work in dual-band, namely X-band and Ka-band, and that should make them according to NASA “extremely flexible for users.” Later LEGS will get an extra, S-band.

This allows for part of the data (including telemetry) to be sent via the X-band, while science data and imagery in high-resolution will be beamed down via Ka-band. Because it can handle a lot more loads, the Ka-band will also be used to support crewed operations on and around the Moon.

NASA calls the new antennas critical infrastructure for its “vision of supporting a sustained human presence at the Moon,” but also a pillar of its Moon to Mars initiative. There is no word yet on when the other three antennas of the system will be ready, or the locations where they will be built.